AIDS and Chimpanzee-Plasma-Derived Hepatitis B Vaccines

Analysis of a 1978 International Symposium

This paper was submitted as a preprint on July 10, 2024, will be submitted for peer review and is available as a PDF:

Update Aug 5: bioRxiv determined the paper was “inappropriate” even as a pre-print. So, I have an updated version I’m now submitting that removes any speculation, doesn’t touch on vaccine safety, and instead, just tries to establish consenses on a simple black & white issue: the mere existence of chimpanzee-plasma-derived Hepatitis-B vaccines.

Abstract

This paper investigates the historical and scientific context of AIDS and chimpanzee-plasma-derived Hepatitis B vaccines, focusing on the proceedings of a 1978 international symposium. Through extensive review of archival documents and recent research, the paper explores potential links between early vaccine trials and the spread of AIDS. The findings highlight discrepancies in public health narratives and call for further scientific scrutiny and transparency. This analysis aims to foster an informed discussion within the scientific community and prompt a re-examination of historical data on vaccine safety and epidemiology.

Open letter to scientists and health officials about AIDS origins

July 12, 2024

Dear Scientists and Health Officials,

The "Factor VIII litigation" revealed that in 1983, U.S. health officials notified pharmaceutical companies that some of their products appeared to transmit HIV. These officials and the companies agreed to bury this information “without alerting Congress, the medical community, and the public.”[1] The companies introduced new, safer versions to their home markets. To avoid discarding the old inventory, they continued selling it in markets with willing buyers, despite knowing it could result in patients contracting AIDS. The settlement agreement led the public to believe that only four pharmaceutical companies were involved, fewer than 10,000 victims were affected, and that each victim's family received $100,000 in compensation.[2]

Fact Mission recently presented evidence hidden from public view in the 748-page, print-only book Viral Hepatitis: A Contemporary Assessment of Etiology, Epidemiology, Pathogenesis, and Prevention : Proceedings of the Second Symposium on Viral Hepatitis, University of California, San Francisco, March 16-19, 1978 (“Viral Hepatitis”).[3] It is not available online, but we can provide a PDF scan of relevant chapters.

A 1982 WHO symposium, available online[4, p. 217], corroborates the decision in that 1978 meeting of public health leaders from the WHO and 13 countries: They decided to sell in low-income markets a new type of Hepatitis-B vaccine that cut costs by substituting chimpanzee blood for human blood following completion of tests on America’s gay community. This contradicts their public statements following the emergence of AIDS among trial participants. This directly involves many scientists central to the COVID origins debate, such as Anthony Fauci, Robert Garry, and Michael Worobey. The data appears to implicate additional pharmaceuticals in the AIDS pandemic, likely administered to millions and manufactured by various companies as well as government agencies.

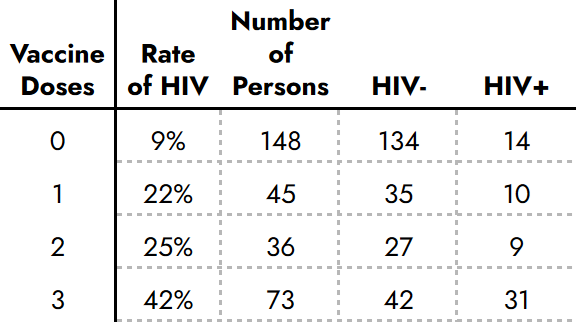

This paper seeks to publicly record our fact-checking requests to those involved and their responses, to assess whether the authenticity of "Viral Hepatitis" is questioned or the accuracy of the following claims is disputed. We aim to highlight apparent inconsistencies and encourage the scientific community to engage, fact-check, and provide counterarguments. This document is not intended to prove vaccine transmission but to foster a thorough examination by experts. If Claim #1 is conceded—that all early AIDS cases in the US had recently been inoculated with a vaccine made from chimpanzee blood and suspected of transmitting live viruses—then the official AIDS origin narrative becomes suspect. The Director of FOIA Appeals and Litigation just wrote that a U.S. agency “has substantial interest in the determination of the appeal” I filed in response to the CDC’s assertion that they cannot locate the data from their own taxpayer-funded trial, despite publicly reporting a 42% HIV rate in trial participants who received the vaccine versus 9% in the placebo group. This raises serious concerns about transparency. All responses will be posted at: https://factmission.org/aids_responses

Private responses can be sent to aaron@factmission.org and will only be published with explicit permission.

If scientists do not challenge the findings or respond with "no comment”, then an important legal question arises from their tacit admission that they may have deceived millions of AIDS victims: Since the statute of limitations generally begins when one becomes aware of a potential claim, did the clock start in the 1980s? Or can the victims’ families still initiate legal action given this new information?

We believe that an open and transparent dialogue is essential for scientific progress and public trust. We invite the scientific community to rigorously evaluate the evidence and engage in this critical discussion.

Sincerely,

Aaron Baalbergen

Introduction

Background and Rationale

The emergence of AIDS in the late 20th century has prompted extensive research and debate regarding its origins. None appear to have considered the administration of Hepatitis B vaccines derived from chimpanzee plasma. Given the overlap in the timeline and populations affected by both, it is critical to explore any possible connections between these vaccines and the spread of AIDS.

Purpose of the Study

This paper aims to investigate the historical context, scientific evidence, and public health decisions surrounding the use of chimpanzee-plasma-derived Hepatitis B vaccines. By examining archival documents, symposium proceedings, and recent research, we seek to identify and analyze claims regarding the potential links between these vaccines and the early cases of AIDS. Our goal is to foster a thorough examination by the scientific community and encourage transparent dialogue, to answer a key question:

During the trials of a chimpanzee-plasma-based vaccine on the gay community, did scientists observe “red bumps” caused by chimpanzee viruses appearing five times more frequently on the men who received the vaccine than on those who received a placebo, dismiss this a sign of vaccine efficacy, and proceed to inoculate the world’s most impoverished communities?

Structure of the Paper

The paper begins with an open letter addressed to scientists and health officials, outlining the purpose of this investigation and requesting their review and comments. Following the letter, we present a proposed timeline and structured list of claims, each supported by detailed evidence and analysis. This format is designed to facilitate targeted feedback on specific aspects of the paper, aiming to clearly distinguish between claims that are conceded and those that are contested. The goal is to prevent a blanket dismissal without consideration, ensuring that each claim is evaluated on its own merits.

Timeline

This paper outlines the following timeline:

1973: Scientists made a prototype Hepatitis-B vaccine for low income markets by using chimpanzee blood instead of human blood, tested on New York heroin users and gay men.

1978: World health leaders agreed to sell it to low-income countries following the clinical trial on U.S. gay men. The first HIV+ blood in the Western Hemisphere was collected among trial participants.

1979: The principal investigator noted a “flareup” 5 times more frequently in trial participants who received vaccine than placebo and it “appeared to be a vaccine-associated event…. With great trepidation, he decided that the trial should go on.”[5]

1980: The CDC began trials on gay men in California, reported another flare-up, blamed on an unidentified type of Hepatitis virus. The inventor “came up with an explanation for the scare… patients receiving vaccine were protected against B and so would only contract and show non-A non-B hepatitis [sometimes diagnosed by ‘red bumps’[6]], this form was bound to appear in higher numbers in the vaccine group.” The “red bumps” were later identified as Kaposi Sarcoma, caused by co-infection with HIV and KSHV. Both viruses were found in archived blood of chimpanzees used in the vaccine’s development. The CDC later provided a breakdown: HIV rates were 5 times higher in the vaccine group than placebo.

1982: The same vaccine was tested in Hangzhou, China.[7] China's first AIDS cases were detected in 1985 in Anhui, about 200 km away, blamed on dirty needles shared with heroin users during plasma donation. However, "There were no intravenous drug users known to the health authorities and police in this area.... people have been diagnosed and reported as having HIV infection and AIDS, including some children and adults who do not have a history of plasma donation."[8]

1983: The New York investigators tested the same vaccine lot in South Africa near the border with Eswatini[9], [10] HIV was first detected in South African black, heterosexuals in 1987 in adjacent KwaZulu-Natal. They had the highest HIV rate in Africa, blamed on sexual transmission[11, p. 67], despite non-vertical, non-sexual pediatric cases.

1984 to present: As blame intensified, officials claimed all vaccine lots were made from human blood, repeatedly pointed to a lack of transmission in areas that received a human blood version to justify the continued sale of chimp blood versions.

Contents

Claim 1: Chimpanzee blood, not human, was the active ingredient in 1970s 2nd generation Hepatitis-B vaccines.

Claim 2: Claims the government added HIV to a vaccine to eradicate gays resulted from obfuscation of the chimpanzee origin.

Claim 3: Some of the chimps carried the ancestor to HIV-1.

Claim 4: Chimpanzee “liver dialysis” was similar to gain of function “serial passaging”.

Claim 5: The rate of AIDS spread among vaccine trial participants exceeded what is expected from sexual transmission.

Claim 6: Health officials withheld key evidence to resolve accusations of vaccine transmission.

Claim 7: The official Haiti narrative is largely irrelevant and statistically virtually impossible based on physical evidence.

Claim 8: Global 1980s AIDS outbreaks correlate with chimp-blood vaccination campaigns.

Claim 9: Vaccination sites were simultaneously co-infected with a 2nd unrelated virus of chimpanzee origin.

Claim 10: The year HIV-contaminated pharmaceuticals were secretly offered to overseas buyers, Congress drafted the bill granting the maker immunity and the leftover chimp-based vaccine was diverted to South Africa’s apartheid regime.

Claim 11: The CDC reported formalin in the vaccine “inactivated” the AIDS virus, however, an internal CDC study found the opposite.

Claim 12: The CDC implied comparable HIV rates in their vaccine vs placebo trial participants, but their only breakdown showed 42% vs 9%.

Claim 13: Robert Garry of “Proximal Origins” claimed 2 ancient HIV+ samples exonerated vaccines. The 1st was exposed as a hoax and retracted. The 2nd was “inadvertently destroyed”.

Claim 14: The CDC now claims they cannot locate the trial data they claimed exonerated the vaccine.

Claim 1

Chimpanzee blood, not human, was the active ingredient in 1970s 2nd generation Hepatitis-B vaccines.

"Viral Hepatitis" documents a 1978 symposium at the University of California, San Francisco. Co-sponsors included the NIH, CDC, NIAID, FDA, and the National Cancer Institute. The hundred participants featured leaders from these agencies, the World Health Organization in Switzerland, the U.S. military, global universities, research institutions, and pharma, mainly Merck. Representatives came from the US, England, France, Germany, Belgium, Switzerland, Australia, Canada, South Africa, the Netherlands, Sweden, Japan, and Costa Rica. The New York Blood Center, which sent the most representatives—Alfred M. Prince, A. Robert Neurath, Cladd E. Stevens, and Wolf Szmuness—announced the breakthrough that is the topic of this paper: their new Hepatitis-B vaccine with a “modified” manufacturing method to reduce cost. This would make it marketable in underdeveloped countries, where many in the general population contracted Hepatitis as infants due to poor infrastructure, but where they could not afford the human-blood vaccines used in rich countries where Hepatitis-B was rare and generally transmitted sexually.[3, p. xvi]

The first generation Hepatitis-B vaccine had been patented in 1969, made from Hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) found in the blood of individuals battling an active infection.[12] “In 1971, Gerin [NIAID], Krugman [NYU] and Purcell [NIAID] prepared a purified HBsAg vaccine of subtype ayw from a unit of blood supplied by Dr. Krugman from a chronic HBsAg carrier at the Willowbrook State School.”[3] The blood came from mentally disabled children intentionally infected with the virus. The NIH funded similar research at Suffolk State School and Wassaic State School, describing the children this way: “Institutions for the mentally retarded serve as an excellent model for study of the epidemiology of the serum hepatitis carrier state… Due to the well known hygienic behaviour of the mentally retarded… longer persistence of the chronic carrier state in mongols.”[13]

Following public outcry, NIAID scientists reported at the symposium the need for a new manufacturing method given “changing social concepts concerning the use of human volunteers.”[3, pp. 494–495].

Unlike traditional vaccines whose active ingredient is grown in inexpensive lab animals, for Hepatitis-B vaccines, it was made from humans as “the chimpanzee is the only suitable non-human animal” that could be infected with human hepatitis. The WHO explained:

“It is currently not possible to collect and process sufficient quantities of plasma to conduct mass immunization campaigns. Secondly, the production and standardization of vaccines is so expensive that the countries which need them most may not be able to afford them…. Moderate quantities can be obtained from the plasma of chronic carriers and from the livers of experimentally infected chimpanzees… ”[14]

Several years before the symposium, those NIAID scientists along with the CDC published in Nature the article “Experimental infection of chimpanzees with the virus of hepatitis B.”[15] In 1980, US government scientists referenced it as citation 52 writing: “The results of these studies and the finding that the chimpanzee is susceptible to HBV infection[52] prompted the development of a second generation of hepatitis B vaccines.”[16] During this symposium, the New York Blood Center presented to health officials from 13 countries the “2nd generation”. This followed their successful patenting of the process and opening their second chimpanzee facility in Liberia, Africa, VILAB II, to expand capacity from their original facility in New York, LEMSIP:

“On the assumption that the most significant utilization of a Hepatitis-B vaccine will be in the prevention of chronic carrier state infection in high-prevalence regions of the world, most of which are in developing nations where vaccine cost is of paramount importance, we have chosen to attempt to develop a highly purified Hepatitis-B antigen vaccine by methods lending themselves to inexpensive, large scale processing by methods conventional in the manufacturer of blood derivatives. A candidate vaccine has been prepared utilizing high-titer e-antigen positive plasma from chronic HBsAG carriers as source material. This vaccine is purified by modifications of methods which have been described in detail (... Journal of Clinical Microbiology 3:626-631; Vnek, J., Ikram, H., Prince, A.M. (1977), Infection and Immunity 16:335-343).”[3, p. 712]

His cited document, first described in 1975 and available online[17], details the “modifications” to the manufacturing process to reduce the cost for the “inexpensive” vaccine to be used in “developing nations”:

“MATERIALS AND METHODS

Source of HBsAg. HBsAg of the adw subtype was purified from pooled plasma of a carrier chimpanzee previously inoculated with plasma from a chronic carrier chimpanzee.”[18]

The use of chimpanzees as both carrier(s) and donor(s) meant the vaccine contained plasma from at least 2 chimpanzees. At the symposium they reported the vaccine was ready for trials on dialysis patients (staff got 1st generation), male homosexuals, military personal, and in areas in Africa and Asia with high rates of Hepatitis-B.[3, Tbl. “50-10”] They had placed these fliers in New York gay bars and bathhouses where they began testing in 1974.[19], [20] Hepatitis-B vaccines for poor countries continued to be made of NYBC’s chimpanzee antigens[21], [22] at least until 1982[4, p. 217] while developed countries got 3rd generation versions, like Merck Heptavax and Pasteur HEVAC-B, that officials assured was made from human blood and screened for HIV[23].

The New York Blood Center’s 1973 patent[24] reveals the transition to chimp blood for 2nd generation versions began that year with a hybrid 53% chimp + 47% human blood vaccines made with the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) and Merck.[3, Tbl. “49-5”] Little is known other than the makers allegedly used heroin users who “lived in flophouses, stairwells, doorways, and fire escapes in New York City”.[25] It’s unclear if the 1973 vaccine was also administered to gay men, as the only vaccine explicitly identified as being given to them was the 1976 version made from pure chimpanzee blood.

The New York Blood Center’s 1976 patent states chimpanzee blood is preferred:

“Plasma used as source material for the purification procedures detailed below is obtained by conventional plasmaphoresis procedures from chronic HBAg carriers. These may be humans or animal species such as chimpanzees in which the chronic HB carrier state can be induced. The chimpanzee offers the practical advantage that it can be infected with human hepatitis B strains of any desired immunologic sub-type, and can develop chronic carrier state infections which in our experience show particularly high titers of HBAg and are frequently associated with high concentrations of both Dane particles and e-antigen. Furthermore, these animals can be conveniently plasmaphoresed at frequent intervals without damage to their health or reduction in HBsAG or e Ag content of their plasma.”[17]

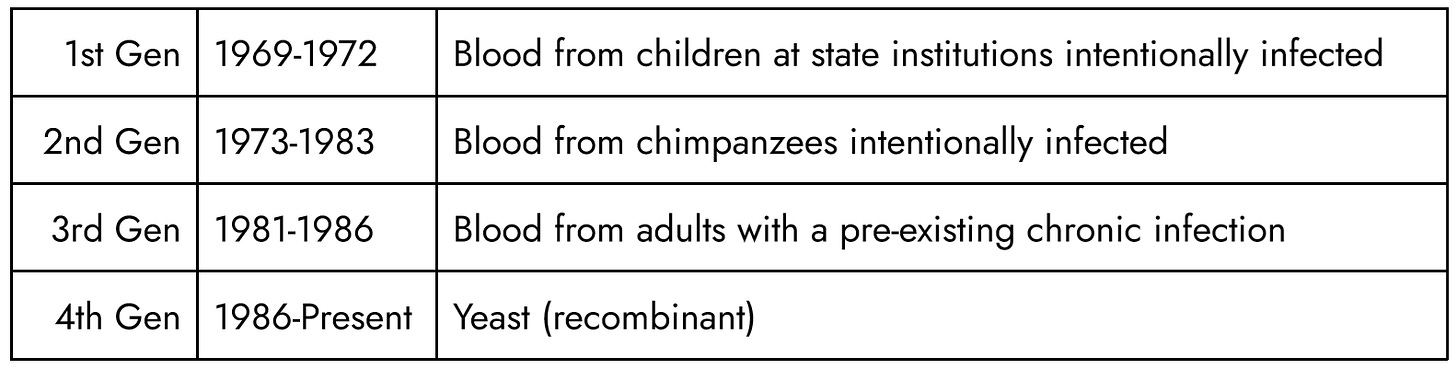

Tracing the lot numbers and manufacturing confirms US government scientists claim that there exist 4 generations of Hepatitis-B vaccines based on different sources for the antigen:

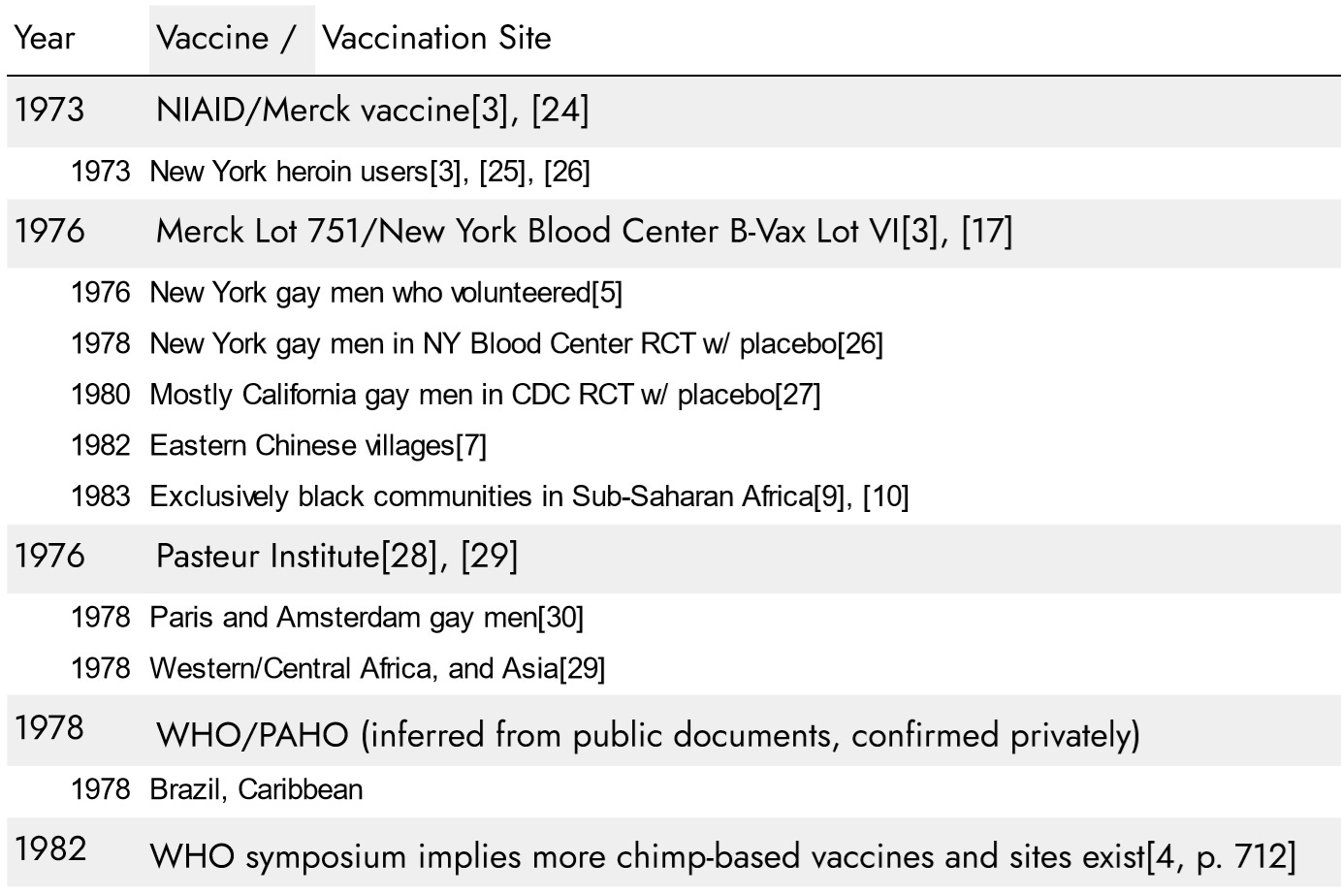

Following are the 2nd generation vaccines and vaccination sites:

At the 1978 symposium, the new NYBC/Merck 1976 vaccine was apparently introduced under 2 different brand names, “NYBC B-Vax Lot VI” and “Merck H-B-Vax Lot 751” as both were announced in parallel, made under the same NYBC patent, and reference the same “adw” antigens.[3], [31] Since 1974, NYBC had tested and archived blood samples from 13,000 gay men in New York to identify 1,083 unexposed to the Hepatitis-B virus to participate in the upcoming trial of the new vaccine.[19] In 1976 and 1977, they administered it to roughly 200 New York gay men who volunteered to try it[5] in advance of formal placebo-controlled clinical trials to begin in 1978. The NYBC trial document states that only gay men received the new inexpensive 2nd generation version intended for “developing nations”, while staff received a different Lot 761:

Two lots of the Merck vaccine, both in alum formulation, are being used: one of sub-type adw (no. 751) in the homosexual trial, and another of subtype ayw (no. 761) in the dialysis trial.[26]

Lot 761 is only mentioned this one time and the antigen source is never specified, however, given the “ayw” subtype, it appears the vaccine given to staff in the dialysis trial was made from the remaining 1st generation human antigens harvested at Willowbrook.[19] There is no mention of “ayw” antigens from any other source, and their papers state that chimpanzees naturally only produce the “adw” subtype given to gay men[32]. The critical point is that the 442 medical staff in the dialysis trial did not receive the same chimpanzee-blood vaccine given to gay men.

The year after the trial ended, doctors began voicing concerns that the vaccine caused the “red bumps” on gay men’s skin during the trial—an early symptom of Kaposi Sarcoma.[33] Rumors spread that two men had already died from the vaccine: San Francisco resident Ken Horne who allegedly contracted the virus at a New York bathhouse when NYBC was inoculating patrons, and New York resident Rick Wellikoff. Cladd Stevens, one of the NYBC employees at the symposium, was part of the team conducting the concurrent trials on gay men and medical dialysis staff. Despite her trial document expressly stating gay men got the new chimpanzee blood version while staff got the human blood version, she asserted that it was impossible for the vaccine to be the cause because “No cases have been reported among the 442 medical staff who were given hepatitis B vaccine two to three years ago in our efficacy trial.”[34] Dr. Donald Francis ran the CDC’s trial focused on California, using the same Lot 751[27], yet he said: “a remarkable vaccine.. this was the old plasma-derived vaccine using carriers of Hepatitis-B–human carriers”.[35]

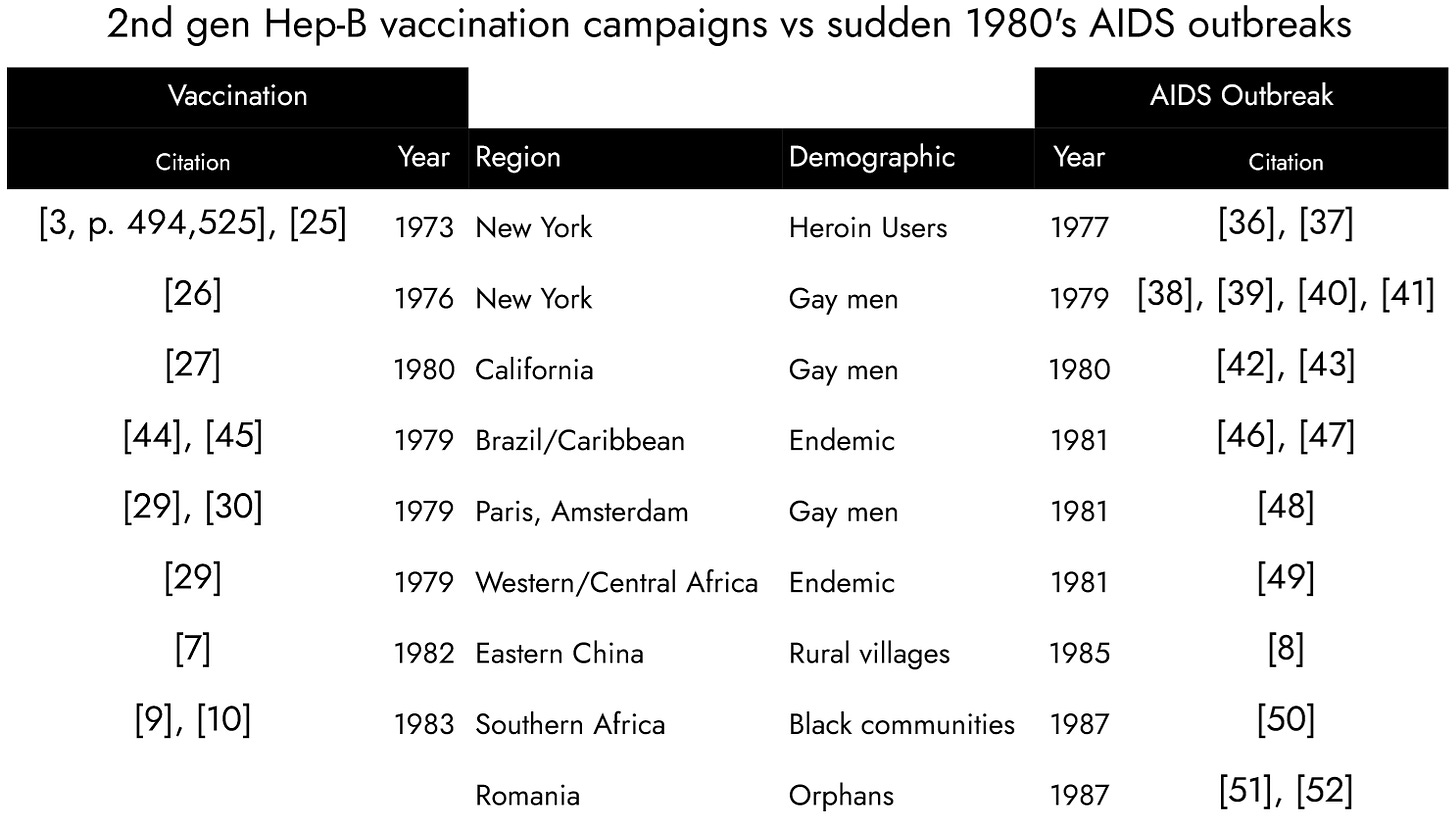

As AIDS outbreaks ravaged in the 1980s, global health leaders, including those at the symposium, deflected allegations that the Hepatitis-B vaccine was responsible by citing vaccination campaigns that were not followed by AIDS outbreaks. However, in each instance, they referenced human-blood vaccine campaigns to refute claims of AIDS transmission from a chimp-blood campaign. If we chart only chimp-blood vaccination sites alongside global sudden AIDS outbreaks, a correlation appears:

The 3rd generation vaccine, made from human blood, Merck Heptavax, was FDA-approved in 1981 and discontinued in 1986. During the gay trials Merck’s original patent for an improved process (4,017,360) was revised to specify plasma came from human donors (4,118,477). Merck’s packaging prominently stated the plasma was human. By contrast, NYBC was heavily invested in the chimpanzees. In 1982, after NYBC scientists were already battling claims their prior generation chimpanzee-blood based vaccines was responsible for AIDS, they doubled-down on chimpanzee blood, reporting at the “Second WHO/IABS Symposium on Viral Hepatitis” in Athens, Greece, 1982 they were shipping a new, updated 2nd generation vaccine: “A new vaccine is reported which contain HBeAg in addition to highly purified HBsAg”. The source material was: “Chimpanzee plasma containing HBeAg and HBsAg”.[4] It appears the only interested buyer was Pieter Willem Botha, head of South Africa’s government. One of the scientists, Dr. Schalk van Rensburg, testified under oath about attempts to reduce black populations on the African continent with weaponized vaccines: “It would not be possible to develop a vaccine that worked on one ethnic group and not the other, it might be possible to skew the delivery of the vaccine along racial lines.”[53]

Five years after the 4th generation Merck Recombivax had made all blood-based Hepatitis-B vaccines obsolete, the WHO reported 3rd generation “Heptavax” was still being administered in Africa[54], but, in one case, the lot number was indicated[10] revealing that what they were calling “Heptavax” was actually leftover 2nd generation chimpanzee blood version made in 1976. The confusion stemmed from officials' refusal to acknowledge the existence of a chimpanzee-blood version. Even as AIDS was beginning to claim more lives than the World Wars, they cited lack of AIDS transmission following the administration of human-blood lots to justify their continued use of chimpanzee-blood lots, always blaming major AIDS outbreaks at vaccination sites on promiscuous behavior.

The New York Blood Center had approximately 200 chimps in the US at LEMSIP and the African expansion in VILAB II facilitated mass antigen production by capturing wild chimpanzees, infecting them with human hepatitis to harvest antigens, and re-releasing to avoid the cost of caring for captive chimps in US facilities.[45], [55] Having two of the world’s largest chimp facilities gave them sufficient capacity for global vaccine production, providing a strong incentive to push forward:

Per the patents[10], [17] a typical bleeding was 7,000 ml of plasma yielding 0.1 to 1.0 mg of antigen per ml. At 700,000 to 7,000,000 µg per bleeding and 40 µg/dose, each bleeding yielded sufficient antigens for 17,500 to 175,000 doses. “Frequent intervals” suggests a minimum of 3 bleedings per chimp, thus 52,500 to 525,000 doses per chimp minimum. NYBC had approximately 200 chimps at LEMSIP in New York, and private communications suggest up to 800 chimps may have been used in the “catch and release” antigen production line in Liberia, giving NYBC likely capacity to vaccinate tens of millions at a minimum in the documented 1970’s campaigns.

The Pasteur documents do not detail the antigen source for the 1970s versions. However, they were made in the years that NYBC was enforcing their patent, and the documents mention working with NYBC[56], and it appears NYBC’s chimpanzee antigens were the only affordable option. The 1970’s Pasteur vaccine was administered to gay men in Paris and Amsterdam[29] and “for the prevention of maternal-infant transmission in the endemic countries of Asia and Africa”.[57]

The WHO/PAHO vaccination campaign can only be inferred from public documents. Brazil reported scouting an antigen harvesting program similar to the one in New York[58], and in Brazil in 1976 the WHO announced seroprevelance surveys would begin in the Caribbean.[44] Haiti was the only high rate country in the Western Hemisphere.[59], [60] The NYBC patent holder’s memoirs describe setting up the VILAB II chimpanzee facility in Liberia to harvest lower-cost antigens for his collaboration with international organizations.[55] Private communications confirm that upon discovering high Hepatitis-B rates in Haiti a vaccination campaign ran around 1978, but this cannot be corroborated with public documents. The 1982 WHO symposium implies more chimp-based vaccines were still being produced for use at unspecified locations.[4, p. 712]

Claim 2

Claims the government added HIV to a vaccine to eradicate gays resulted from obfuscation of the chimpanzee origin.

Many vaccines were proven to transmit viruses from the animals used in their manufacturing, such as various simian viruses in polio vaccines, avian leukemia virus in the yellow fever vaccine, and porcine circovirus in the rotavirus vaccine. Vaccine transmission would have been uncontroversial if officials had acknowledged that, during their trial of one derived from chimpanzee blood, participants' skin erupted with “red bumps” from the simultaneous coinfection of two chimpanzee-origin viruses: HIV and Kaposi’s Sarcoma Herpes Virus.[37], [61] However, by the time AIDS was recognized in 1982, those spots had progressed into a novel, lethal cancer that claimed the lives of several participants. Nearly half were infected.[62] By that time many pharmaceutical companies, governments, and NGOs had already administered similar 2nd generation vaccines to Europe's gay community and in underdeveloped regions where non-sexually transmitted Hepatitis-B was endemic–and AIDS was now emerging. NYBC was continuing to make chimpanzee-based versions.[4, p. 712]

Health officials had put in writing their acceptance of legal liability. During the trial’s first year in New York, the scientist running it, Dr. Wolf Szmuness, noted a “non-a non-b flareup”, which was how they described ‘red bumps’ not caused by Hepatitis[6], and “11 occurred among vaccinated people, two among the placebos” With that 5 to 1 ratio it “appeared to be a vaccine-associated event.”[5] Dr. Francis' San Francisco trial followed the dismissal of the 1979 "red bumps" in New York trial participants as coincidental. He described the same occurrence in San Francisco, which was again dismissed: “Dermatologists like Mark Cohen in San Francisco and others in New York who said I'm looking at these guys and suddenly they come in with with these Kaposi Sarcoma lesions… except for these red bumps on their skin are otherwise healthy”.[35]

Of the first New York trial, Dr. Szmuness wrote: “I wanted to stop the trial at once because the basic principle of any clinical experiment is not to do harm to the participants. Their interests are always of the first importance. You should not - you don't have the right to - harm them.” The book continues: “With great trepidation, he [Dr. Szmuness] decided that the trial should go on”, based on his colleagues’ assurances of an innocent explanation. He wrote: “If I am wrong, I'll go to jail. My scientific career will be in shreds and I will be faced with an enormous amount of litigation as well." His colleagues, Aaron Kellner, Cladd Stevens, and Saul Krugman “reassured and teased him” that “if the problems were real they'd pay the lawyers, take care of Maya [his wife], bring him food and flowers in jail… They would, Kellner assured him, tap the best lawyers in the United States”.[5]

The year those “red bumps” were recognized as AIDS, Dr. Szmuness was, in fact, jailed for “deranged behavior”[63] blamed on a brain tumor and dead a few months later, right before Dr. Stevens confirmed all New York participants with AIDS had received vaccine, not placebo[34]. She wrote for his eulogy: “Throughout the entire two years of the trial in homosexual men he told us over and over again at monthly meetings, that the study was a disaster and demanded an accounting for each of more than 1,000 men in the study”.

Even in hindsight, scientists rationalized continuing the trial. These interviews from around 1981, recalling the 1979 "flare-up," were published in 1985 by June Goodfield after half the participants were dying of AIDS. The book quotes Dr. Purcell, author of the 1972 paper “Experimental infection of chimpanzees with the virus of hepatitis B” and co-developer of the chimpanzee-blood-based vaccine: “Afterward [after the trial] Dr. Bob Purcell, of the National Institutes of Health, came up with an explanation for the scare… patients receiving vaccine were protected against B and so would only contract and show non-A non-B hepatitis [then diagnosed by “red bumps”], this form was bound to appear in higher numbers in the vaccine group.”

We recently showed a scientist associated with the trial that the CDC reported the HIV rate was five times higher in the vaccine group than placebo (Claim 12). It appears they concluded this demonstrates the effectiveness of the vaccine: the trial participants who received the vaccine were healthy and on sex tourism holidays in Haiti where they contracted HIV, while those who received the placebo were sick in bed battling Hepatitis infections.

The author of the 1985 book repeated the claim the vaccine was made from human blood and apparently accepted Dr. Purcell’s innocent explanation, writing: “Success was due both to the existence of a superb vaccine and to the design and execution of the trial. This was not only the most complex ever in the history of medicine, but was also the most impeccable.”

Following is an excerpt from the 1988 book Wikipedia lists under “Discredited HIV/AIDS origins theories.”[64] Note the only materially inaccurate statement is “The vaccine was manufactured from the combined plasma of 30 highly selected gay men who carried the hepatitis B virus in their blood”.[65] Based on that false premise that it was made from the blood of gay men before AIDS entered the gay community, HIV would have had to have been added. That fallacy led to the incredible, conspiratorial question: “Was the AIDS virus introduced into gays with the hepatitis B experimental vaccine?” Health officials had little difficulty convincing the public they would never intentionally add a primate virus to the vaccines. Had they admitted that the makers feared the vaccine transmitted live viruses and that, like the primate-based polio vaccines which exposed tens of millions to various primate viruses, this vaccine was also developed using primates, transmission of a new primate virus would have been an obvious concern rather than a “conspiracy theory”.

“Promiscuous gays were avidly sought as volunteers to test the efficacy of a newly developed hepatitis B vaccine manufactured by Merck and the National Institute of Health (NIH). By 1977, over 13,000 Manhattan gays were screened to secure the final 1,083 men who would serve as guinea pigs to test the hepatitis B vaccine…. Through AIDS antibody blood testing of pre-1978 stored blood, the scientists proved that THE NEW AIDS VIRUS DID NOT EXIST IN AMERICA BEFORE 1978. There was complete agreement that the AIDS virus had been "introduced" into the United States through the male homosexual population in Manhattan sometime around the years 1978-1979… The origin of HIV and the KS virus came out of the experimental hepatitis B vaccine trials (1978-1981) in which thousands of healthy gay men were injected with an experimental Vaccine. In the United States, the earliest positive HIV blood tests were discovered in samples of blood donated by male homosexuals in New York City, as part of this experiment. There was no "incubation period" for HIV in the United States, the earliest HIV+ blood specimens were from 1978 - the same year the first gay hepatitis B experiments took place in Manhattan, at the New York Blood Center…. In January 1979, two months after the hepatitis B experiment began, purple skin lesions began to appear on the bodies of young white gay men in New York City…. [In 1980] Rick Wellikoff, the 37 year old, 5th grade teacher passed away… The vaccine was manufactured from the combined plasma of 30 highly selected gay men who carried the hepatitis B virus in their blood… Was the AIDS virus introduced into gays with the hepatitis B experimental vaccine?”

Claim 3

Some of the chimps carried the ancestor to HIV-1.

The New York Blood Center established the Laboratory for Experimental Medicine and Surgery in Primates (LEMSIP) in 1965. There are no published results available for HIV testing of their chimpanzees. However, among the chimpanzees imported at that time and housed in a different facility was "Marilyn". She was captured in 1963 and belonged to the Pan troglodytes troglodytes (P.T.T.) subspecies considered the origin of HIV-1. Her archived blood tested positive for HIV in 1985, and subsequent genetic sequencing identified it as the SIVcpzUS variant:

“Marilyn was wild caught…presumed to have been infected prior to capture in 1963”[66]

“Marilyn's HIV-1…which we termed SIVcpzUS… HIV-1 groups M and N were roughly equidistantly related to SIVcpzGAB1, SIVcpzGAB2 and SIVcpzUS”[67]

Claim 4

Chimpanzee “liver dialysis” was similar to gain of function “serial passaging”.

LEMSIP was the US’s leading chimp research facility, providing chimpanzee organs for human transplant, and, since 1966, for cross-circulation, connecting intravenously chimpanzees and humans of the same blood type so the chimps’ livers could purify the raw mixed blood flowing between the species.[68] Other US chimpanzee facilities also cross-transfused raw human+chimp blood between the species.[69]

Similar to the “serial passaging” in gain of function experiments, this allowed the chimp virus to adapt to a new host environment by passing time in humans. The chimp care manuals suggest each chimp was used repeatedly to treat multiple human patients, and it appears each human required multiple sessions.[70] Thus, if one of the “liver dialysis” chimpanzees was the source of the blood used in the vaccine, that blood may have been a mixture from many humans and chimpanzees, containing viruses that had been transfused back and forth between species for a decade.

It appears that the New York Blood Center (NYBC) has never disclosed which chimpanzee(s) provided the blood that was injected into gay men whose blood tested positive for HIV months later. Additionally, they have not released test results from that chimpanzee’s blood, nor for the B-Vax Lot VI/H-B-Vax Lot 751.

Important questions remain unanswered:

What viral strains did the LEMSIP chimps carry?

Could they have evolved into something closer to HIV-1B during "liver dialysis"?

Were any of the chimps used in other experiments, like Dr. Gallo’s virus cancer program, combining retroviruses in the AIDS family, and testing lethality on chimps?

Does this explain what apparently unknown pathogen caused men at trial sites to develop Kaposi Sarcoma without HIV[71], while other men suffered AIDS trademark immune-system collapse also without HIV?[72]

Claim 5

The rate of AIDS spread among vaccine trial participants exceeded what is expected from sexual transmission.

Retroactive testing of the blood samples collected from 13,000 New York gay men pre-screened starting in 1974[19] was HIV-negative.[38], [73] In 1978, the year the formal trial began following prior vaccination of approximately 200 volunteers, men in the trial began testing HIV-positive[38], suggesting that HIV entered the community around 1977 or 1978, confirmed by the CDC:

Previous analysis of subjects in this cohort who seroconverted suggested that the first seroconversions occurred in 1977.[73]

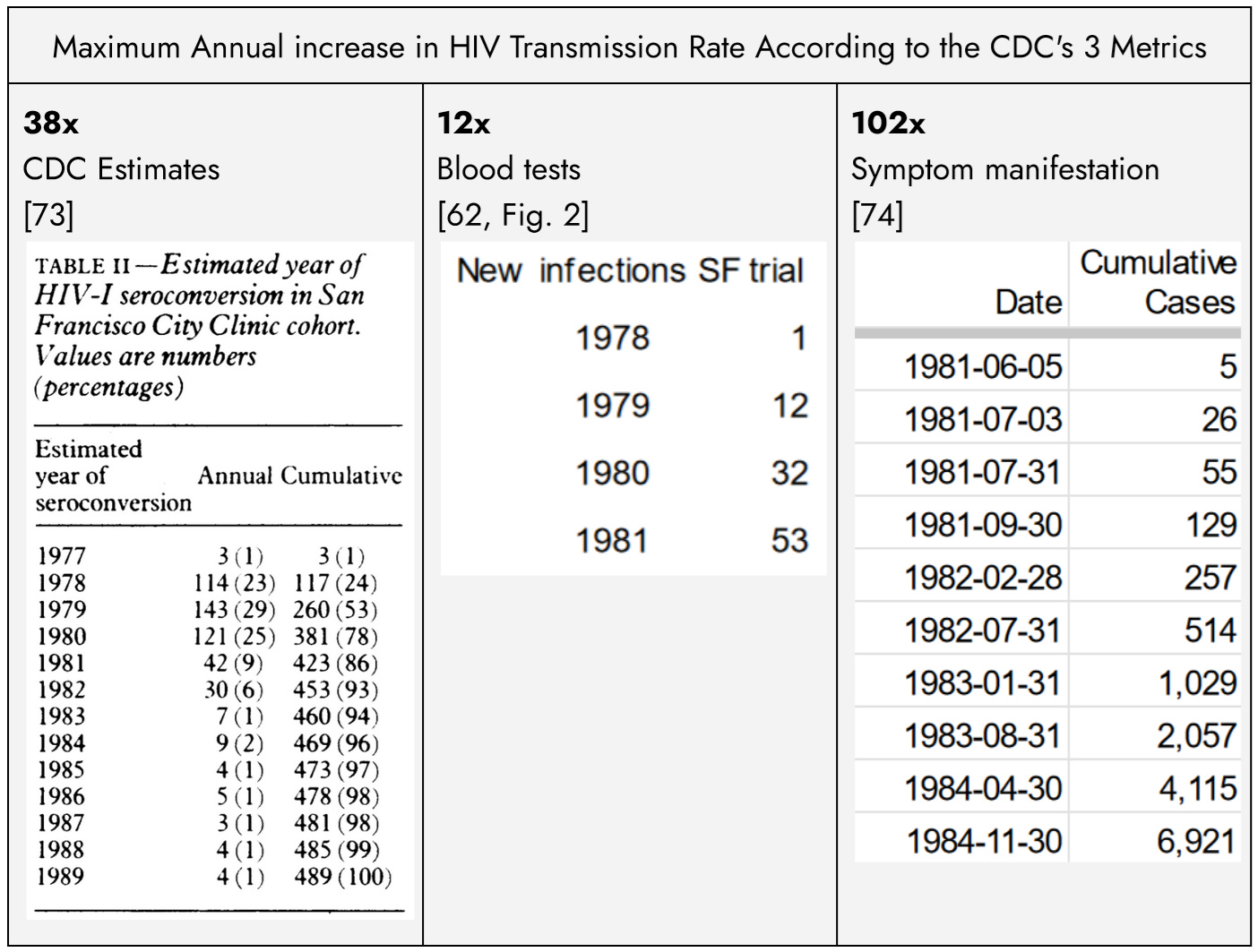

The risk of HIV transmission is commonly estimated at 1 in 500 per unprotected sex act. Assuming a highly promiscuous population engaging in unsafe sex 1 or 2 times per day, each HIV-positive individual would, on average, infect approximately one other person per year, leading to an annual doubling of the HIV-positive population. However, every CDC metric for the early spread of HIV in the US gay community exceeds the expected rate from sexual transmission alone, even during the acute phase:

Even scientists like Michael Worobey, arguing for a natural origin, concede HIV must have been mass introduced from an external reservoir:

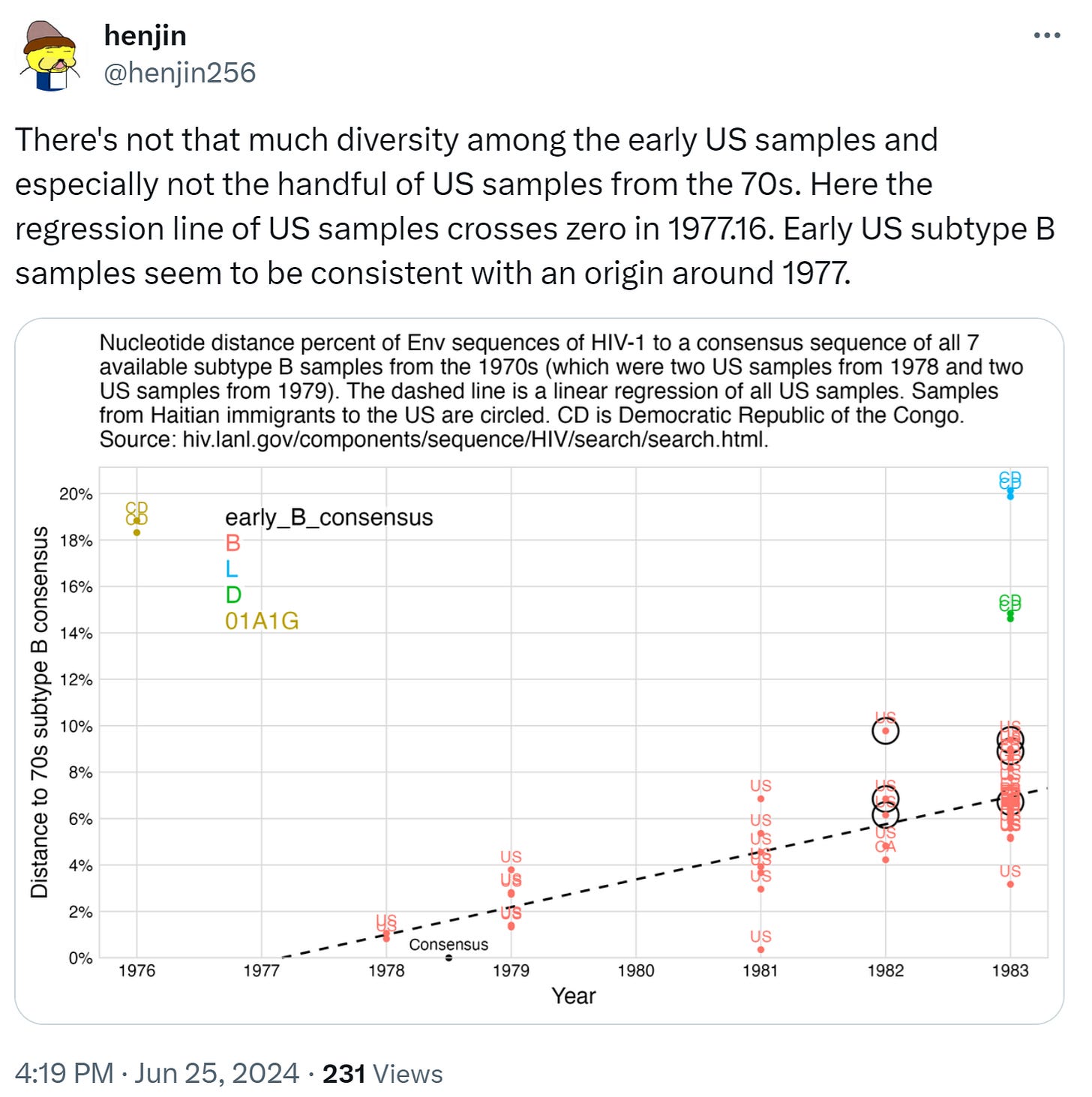

“The emergence of HIV-1 group M subtype B in North American men who have sex with men was a key turning point in the HIV/AIDS pandemic. 1978–1979—eight of the nine oldest HIV-1 group M genomes to date. The extensive genetic diversity in New York in 1978 can be explained, ONLY, by several years of circulation of the virus before.”[38]

Claim 6

Health officials withheld key evidence to resolve accusations of vaccine transmission.

The official chosen to lead the government’s response, Anthony Fauci, directed the agency that helped develop the chimpanzee-blood based Hepatitis-B vaccine, and those who administered the vaccine were chosen to determine if it was responsible for AIDS. Suspicions arose immediately when AIDS was recognized in 1982 after 41 gay men in New York and California developed Kaposi Sarcoma[43]. Doctors noted that every case appeared at a vaccine trial site:

“The clustering of cases in New York City, Los Angeles, and San Francisco suggests a local factor. It has occurred to me that the hepatitis B vaccine trials used homosexuals in these communities as subjects. In view of the coincidence of the outbreak…were any of the patients involved in the hepatitis B vaccine trials?”[33]

Dr. Cladd Stevens, who attended the symposium and promised to pay the legal bills if the symptoms in trial participants was caused by the vaccine, responded: “There are no cases among persons in other groups who have gotten vaccine in immunogenicity or efficacy studies, such as medical personnel and dialysis patients.”[33] However, she would have known her team gave medical personnel and dialysis patients a different vaccine lot, made from human blood.[26]

She continued: “None of the patients with Kaposi's sarcoma were participants in the hepatitis B vaccine trial. Therefore, we do not think that the epidemic is caused by or related to the vaccine…. We expect that some patients with acquired immune deficiency and Kaposi's sarcoma have received the vaccine because they are in the group known to be affected.”[33]

However, Dr. Stevens’ colleague wrote “The total number of deaths identified in the cohort for the years 1978-1988 was 998… This study illustrates the enormous toll the AIDS epidemic has taken on a cohort of homosexual men in New York City.”[20]

The difference might be attributable to Dr. Stevens’ ambiguous expectation that “some” of the then-current NY AIDS cases “received the vaccine”, while claiming that none were “participants in the hepatitis B vaccine trial”. It leaves open the possibility that some of the early NY AIDS cases were among the approximately 200 men that her team vaccinated in 1976 before the formal 1978 trial. The death of 2 men was already being blamed on the vaccine, Rick Wellikoff, a New York resident, and Ken Horne, a San Francisco resident who allegedly was infected in a New York bathhouse around the time Dr. Stevens’ team was inoculating patrons[75], but she does not clarify if they were given the vaccine.

The vaccine would be implicated if “some” early cases were among the approximately 200 men she vaccinated per-trial given those men likely represented around 0.02% of New York’s population. The San Francisco Health Department was more specific: six of 10 were participants in their local cohort,[76] although, again, imprecise wording leaves open the possibility that the other 4 might include San Francisco residents like Horne who some claimed contracted the virus from the vaccine in New York. Dr. Stevens’ wording leaves open the possibility New York AIDS victims received the vaccine, while giving the impression that was not the case.

The year Dr. Stevens made that comment, the same Lot 751 was administered in Eastern China, and the following year, she also used it in a trial with South African apartheid-era scientists. They administered it to the Swazi[10]–a group of rural, conservative, Christian farming villages known for their strict prohibition of sex outside of marriage.[77] Just like U.S. gay men, both the Chinese villages and the Swazi suffered AIDS outbreaks from the new HIV-1B variant 3 to 4 years after inoculation, and the Swazi became the hardest hit in Africa, with 40% of the population infected.[78]

Apparently referring to those Chinese villages, Dr. Francis said: “We collaborated a lot with the People's Republic of China and Thailand how to immunize kids in the newborn period... Essentially eliminated the terrible disease of hepatitis-B. Remarkable! I mean look at my experience. I ended up working in the United States let's say for the gay male study but doing an awful lot of my Hepatitis-B work outside advising WHO... CDC had a very close relationship with WHO, and then had its own collaboration around the world so CDC... How wonderful CDC will be and can be... they could really think big. Then the history gets more difficult with HIV because the politics..."[35]

They administered in China the same Lot 751 after accusations it caused AIDS. Paul O’Malley, a San Francisco Health Department official wrote: “Several gay newspapers and individuals started postulating that the hepatitis B vaccine might have been a government plot to infect the community with HIV…. This rumor was completely shot down, because once we started testing old blood specimens, we could clearly show that people were infected with HIV in '78, '79, before the first gay men had received the hepatitis vaccination, and we clearly showed that the prevalence of HIV was actually less in the men in the vaccine trial than in the larger population.”[79]

The existence of HIV (in Africa) before the development of the vaccine does not rule out the possibility of vaccine transmission. Additionally, his claim that HIV’s emergence in the Western Hemisphere in 1978 predated the trials is contradicted by the trial documents: “the first [New York] participant was inoculated in November 1978”[80] and some men were vaccinated in 1976 and at least one of the early cases purportedly contracted the virus in New York.[75] Further, an article in Jama published in March 1979 claims the CDC was already beginning to administer the vaccine in their trial that included San Francisco.[81]

O’Malley co-authored another paper confirming that, 2 years after New York volunteers were vaccinated, 1 man in the San Francisco cohort was HIV-positive in 1978. As a result he dismissed as coincidence his data showing that at the end of the trial, 42% of the participants were infected, and the infection had spread to thousands within the community.[62] Scientists argued the rapid rise of infections in New York suggested mass introduction from an external reservoir, allegedly Haiti, but there is no evidence that gay men in San Francisco regularly traveled to Haiti. His extraordinary claim that the HIV rate was even higher (i.e. over 42%) in the “larger population” also cannot be reconciled with his own paper. He labels a group of gay men excluded from the trial for previous Hepatitis-B infection as higher risk given the “behaviors that increased the risk for hepatitis B virus transmission also increased the risk for acquired immunodeficiency syndrome.”[62] Yet in that “higher risk” group the HIV rate was 23% when the trial ended vs 42% among the “lower risk” participants.[82]

As will be demonstrated in claim 12, the CDC made a similar claim about a lower rate of transmission in trial participants, but it appears to be based on observing that after the trial ended the rate of newHIV infections in that “higher risk” group excluded for an STD history unsurprisingly exceeded the “vaccine recipients”.[83]

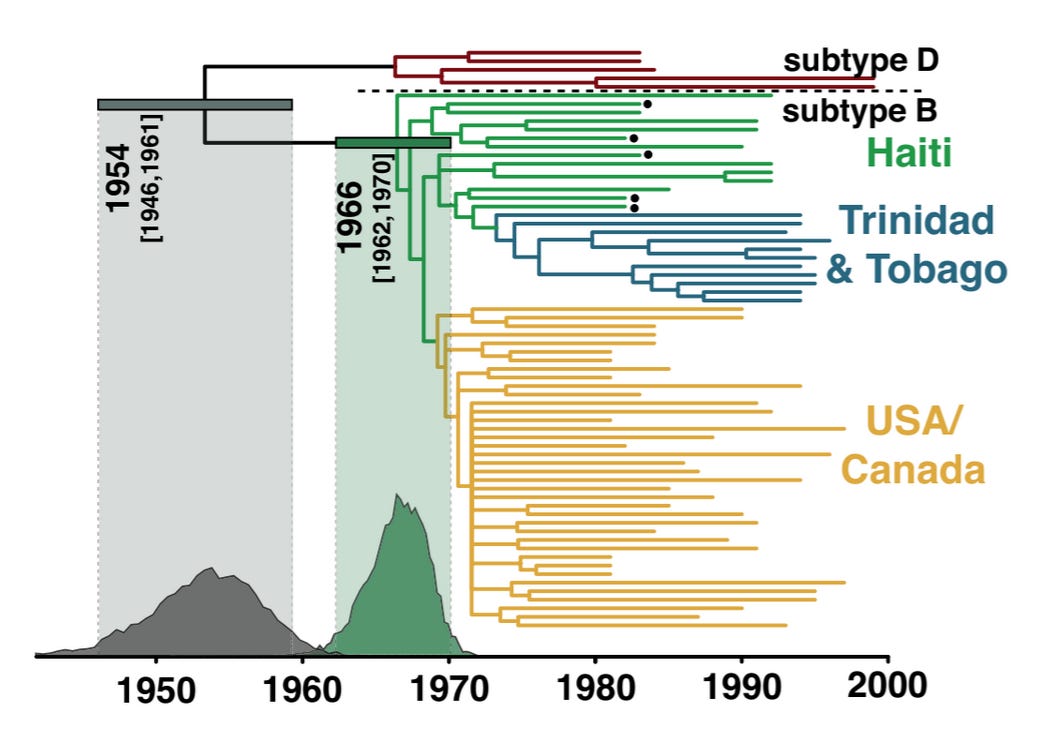

Claim 7

The official Haiti narrative is largely irrelevant and statistically virtually impossible based on physical evidence.

This paper acknowledges that HIV existed prior to the emergence of AIDS in New York in 1978 and had been slowly spreading and evolving. However, this does not rule out the possibility of vaccine transmission. It is evident that the Hepatitis-B virus was present in Haiti before the vaccine. Vaccine manufacturers concede that the higher rate of Hepatitis in trial participants who received some lots of vaccine compared to those who received a placebo indicates those lots transmitted the Hepatitis-B virus. In contrast, for HIV, the stark difference between the vaccine and placebo rate is disregarded. Instead, manufacturers argue that if scientists can find indirect evidence suggesting that HIV might have existed undetected in the Western Hemisphere before the vaccine, this somehow absolves the vaccine.

HIV evolves rapidly and many subtypes existed long before its emergence in New York. The first confirmed African HIV+ samples were:

1959 HIV-1 subtype D

1960 HIV-1 subtype A

1966 HIV-1 subtype C

There exist only 3 laboratory-confirmed deaths from HIV pre-dating AIDS US emergence. All 3 contracted the virus in the early 1960’s near its African epicenter in the Congo and died between 11 and 20 years later:

Arvid Noe and family HIV-1 subtype O

Grethe Rask HIV-1 subtype D

"Dr. Bryceson's patient" HIV-2

HIV-1 is divided into groups M, N, O and P. Group M alone has subtypes A, B, C, D, F, G, H, J, and K. HIV-2 has 8 groups.

If the early AIDS cases in the US and Haiti arose from organic sexual spread, many subtypes would have been found gradually increasing throughout the 1970’s. Instead, there were zero HIV samples collected in the Western Hemisphere as of 1977. And in 1978-1979 there was an explosion of samples and all were the new HIV-1B subtype never seen before. That is best explained by a mass introduction in 1978. Dr. Worobey’s paper asserts that the “extensive genetic diversity in New York in 1978 can be explained, ONLY, by several years of circulation of the virus before”[38], yet that is contradicted by his acknowledgement that all 1978-1979 samples were of subtype 1B. Besides, following the chimpanzees’ use for 10 years of liver dialysis treatment they could have carried a mix of blood and viruses from many chimps and humans evolving since the 1960’s. Regardless, the genetic sequences are publicly available in the Los Alamos National HIV Data, and independent researchers have put them on charts challenging the claim of diversity even within the subtype B:

The 1973 patent suggests a chimpanzee-based lot was apparently tested in New York that year. The initial 1975 filing of the second patent describes another batch of antigens used in trials involving gay men until 1981 and notes that the same chimpanzees could be repeatedly bled for vaccine production. Any lot administered in Haiti might have used antigens from different chimpanzees or the same chimpanzees harvested years later. Phylogenetic studies assume a zoonotic event followed by organic evolution in humans, without considering that variations could result from evolution in chimpanzees followed by repeated mass introductions. Using phylogenetic studies to disprove vaccine transmission may be considered circular logic, as it starts with the assumption that it aims to prove.

Even if HIV were present in the US or Haiti before 1978, it does not disprove the possibility of vaccine transmission. However, the inability to find HIV+ samples strengthens the case for vaccine transmission. This lack of samples is not due to a lack of effort. For instance, Robert Garry received $17 million in grants following his purported discovery of a pre-1978 sample, which was later discredited (claim 13).

In 1984, just a few months after scientists announced they thought they had found a causal virus, before there was a test for it or anything was known about subtypes or transmission rates, Dr. Anthony Fauci had already concluded Haiti was likely the external reservoir from where New York gay men contracted the virus:

“It is very likely that the male homosexuals in New York City, who frequently travel to Port au Prince in Haiti for vacations and for sexual contacts down there, picked up the virus in Haiti.”[84] Dr. Anthony Fauci, 1984

Years later, after scientists complained of intense pressure to adhere to the government’s single narrative, Dr. Michael Worobey tested the hypothesis:

“To test these hypotheses, we recovered complete HIV-1 env and partial gag gene sequences from archival specimens collected in 1982–1983 from five Haitian AIDS patients, all of whom had recently immigrated to the United States and were among the first recognized AIDS victims.”[85]

However, Dr. Worobey overlooked the physical evidence:

Haiti’s role as one of America’s principal suppliers of donated blood in that era means ~1 million Americans were transfused with Haitian blood while it was supposedly spreading in that country.[86] Yet there exists not one report of contracting the virus from Haitian blood before its emergence in trial participants. Archived Haitian blood was tested and found negative prior to HIV-1B’s emergence in the US.[87]

Dr. Worobey arrived at his conclusion after testing samples from 5 Haitian AIDS patients in the US in 1982-1983 after AIDS was already ravaging the gay community. The earliest possible infection in the gay community was 1977, and some infected in 1978 developed the trademark Kaposi Sarcoma “red bumps” the following year. Both Haitian doctors and American doctors treating Haitian immigrants claim they never saw this condition in Haitians before AIDS emerged in the gay community[87]. Dr. Worobey does not explain why he assumes Haitians had been infected nearly 20 years prior but they had a nearly 10x longer incubation period before symptoms appeared.

The same problem exists for Dr. Worobey’s critics arguing New York gay men brought the virus to Haiti.[87] It’s hard to explain how the virus entered the New York gay community in 1977 or 1978, and 1 year later they had infected such a large number of Haitians through sexual spread.

It appears the only explanation for the nearly simultaneous, explosive emergence of exclusively the new HIV-1B subtype in New York and Haiti is a nearly simultaneous mass introduction. While claims of a WHO/PAHO 1978 vaccination campaign in Haiti cannot be verified with official documents, as explained in Claim 1, it is alluded to and arguably the only explanation that aligns with the physical evidence.

Claim 8

Global 1980s AIDS outbreaks correlate with chimp-blood vaccination campaigns.

Building on the subtype argument in claim 7, the new HIV-1B subtype emerged in trial participants who received lot 751 in 1978. Lot 751 is uniquely documented for its global use over a span of a decade. In every instance, across the Americas, Africa, and Asia, not only did an AIDS outbreak occur four years after inoculation with lot 751, but it was also consistently the same 1B subtype in each case.

HIV-1B occupies a vital position in various continent epidemiological profiles and successfully been dispersed across the globe. It is currently the only subtype circulating in several countries of each continent all over the world.[88]

The villages in Eastern China inoculated with Lot 751 in 1982 suffered a 1B outbreak 3 to 4 years later.[89] However, the 1B outbreak among the Swazi in 1987 following their 1983 Lot 751 inoculation is more difficult to dismiss. Unsurprisingly South Africa’s first AIDS cases among gay, white, urban flight attendants returning from the US carried 1B[90], [91]. South Africa’s first infected black heterosexuals lived far away in rural farming villages that were vaccinated against endemic Hepatitis-B, yet it appears they also carried the new 1B that emerged in the US rather than earlier subtypes already circulating in other black communities.[88]

It would be interesting to compare the differences in the 1B that emerged in the Swazi 4 years after their 1983 Lot 751 inoculation to the 1B that emerged in New York following their Lot 751 inoculation 7 years prior. Unfortunately, it appears only one black heterosexual sample was sequenced in 1987, it’s unknown if it was among the Swazi, and there are no details to the claim: “There have been cases of heterosexual HIV-1 B described within our laboratory (Dr. Jacobs, personal communication).”[88] However, a couple years later when HIV had taken hold in South Africa, most cases were subtype C. It would be interesting to know what vaccine lots those communities received, but that information does not appear to be available.[9], [10], [92]

When AIDS emerged in Africa’s black heterosexuals, doctors noted “HIV infections in sub-Saharan Africa not explained by sexual or vertical transmission… HIV infections in African adults with no sexual exposure to HIV and in children with HIV-negative mothers.”[93] HIV rates did not correlate with other sexual diseases, and most cases reported being in monogamous relationships or having no recent sexual activity[93]. Dr. Fauci dismissed this by saying “if you examine the infants with AIDS, and their mothers, the mother in three out of four cases has the virus in an asymptomatic way.”[84] He provided no explanation for the other 1 in 4 infants, nor did he acknowledge the vaccine was given to both pregnant women and newborns “for the prevention of maternal-infant transmission in the endemic countries of Asia and Africa”.[57] Further, among the Swazi, at one point nearly half of new mothers were HIV+.[94] Most new infections were reported in women reporting monogamous relationships[95] and, uniquely in African communities, the HIV rate was far higher in women[94]. If it were a part of their culture, one would expect that HIV would have spread much earlier. Yet, 20 years after HIV’s first confirmed emergence in Kinshasa in 1959 it had barely spread beyond Kinshasa’s prostitutes. In that city only 11% of prostitutes were infected as of AIDS emergence in the 1980’s, and the retroactive testing of archived blood showed that rate had been steady for 10 years, and less than 1% of the general population was infected[96]. In advance of giving these Hepatitis-B vaccines, blood samples were archived in 7 neighboring Sub-saharan countries to measure Hepatitis-B prevalence, and retroactive testing in 1990 found all HIV-negative, leading scientists to question whether HIV even originated in Africa.[97]

Yet following vaccination, HIV spread among Africa’s black heterosexuals at a pace comparable to that among the young gay men recruited from New York bathhouses, selected for being the most promiscuous. Claim 5 demonstrated that even within the New York group, the spread of HIV was beyond what one would expect from sexual spread.

Claim 9

Vaccination sites were simultaneously co-infected with a 2nd unrelated virus of chimpanzee origin.

The majority of early AIDS cases at US trial sites developed Kaposi Sarcoma–a cancer that can only occur with the simultaneous co-infection of HIV and a second unrelated Kaposi’s Sarcoma Herpes Virus (KSHV aka HHV-8).[37], [98] The closest ancestor to KSHV is PtRV-1, which also originated in the same “PTT” sub-species of chimps that provided the blood for the vaccine. The chimps with HIV also carried KSHV/PtRV-1.[61] KSHV is an oral virus, not found in sexually transmitted body fluids. So while it’s theoretically possible to transmit both viruses simultaneously from sex and kissing, the dual infection was rarely seen outside cities that were not vacation sites. Especially in the US, outside vaccination sites, AIDS cases were mostly HIV only.[98] Nearly all cases appeared during the incubation period of trial participants, and largely vanished as the participants died off.[99] Unlike HIV, Kaposi's Sarcoma Herpes Virus did not correspond to sexual activity.[98]

Claim 10

The year HIV-contaminated pharmaceuticals were secretly offered to overseas buyers, Congress drafted the bill granting the maker immunity and the leftover chimp-based vaccine was diverted to South Africa’s apartheid regime.

Vaccine manufacturers had already been lobbying for legal immunity. But in 1983, Maurice Hilleman, Merck’s vaccine head who made Lot 751 with the New York Blood Center, wrote a paper entitled “Vaccine development: An Industrial Point of View” which his CEO took to Congress testifying that vaccine "manufacturers have been held responsible… even though the vaccination program was controlled and run by public health officials.”[100] In November, 1983 Congress drafted the National Vaccine Injury Compensation Program ultimately granting Merck full immunity.[101]

That same year the same scientists who ran the gay trials reported the leftover 1976 Lot 751 from the trial was administered in Kangwane, South Africa, to the Swazi.[10] That same month, the apartheid regime greenlit a program called “Project Coast”, ultimately spending $3 billion[102], [103] on the project that scientists testified under oath included reducing black populations with weaponized vaccines[104], and according to an employee, involved an AIDS-transmitting vaccine.[105] The “highly motivated” apartheid regime was praised for “enthusiastic support” of an “unpublished WHO expanded programme" to administer that same vaccine to exclusively black communities across Southern Africa.[54] Next door to the Swazi, sharing a similar demographic, was Venda[54]. Whereas the Swazi were the first to get the vaccine and the first and hardest hit with AIDS, Venda was the last to get the vaccine in the early 1990’s. At the time of the rollout Venda was the “least affected” district[106], but following the campaign HIV rates went from 0.64% to over 12%.[107]

Claim 11

The CDC reported formalin in the vaccine “inactivated” the AIDS virus, however, an internal CDC study found the opposite.

In the CDC’s 1986 paper "The Safety of the Hepatitis B Vaccine Inactivation of the AIDS Virus During Routine Vaccine Manufacture" Dr. Francis defended his continued use of it:

“In the United States, one hepatitis B vaccine (Heptavax-B) has been licensed for the prevention of hepatitis B virus infections. Even though this vaccine has been shown to be highly effective and well tolerated in controlled trials and has been recommended for use in those at risk for acquiring infection by hepatitis B virus, many individuals have been reluctant to be immunized for fear of contracting acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). In this study, we demonstrate that

(1) each of the three inactivation steps used in the manufacture of Heptavax-B independently will inactivate the infectivity of high-titered preparations of the AIDS virus;

(2) recipients of the hepatitis B vaccine do not develop antibodies to the AIDS virus;

(3) the hepatitis B vaccine does not contain detectable levels of nucleic acids related to the AIDS virus.

These observations clearly demonstrate that vaccination with the currently available hepatitis B vaccine poses no demonstrable risk for acquiring AIDS… Each of the three treatments, pepsin at pH 2, 8M urea, or 0.01% formaldehyde, completely inactivated all isolates of the AIDS virus.”[108]

The “currently available hepatitis B vaccine” they tested was 3rd Generation, made from the blood of the gay men who received the 2nd Generation vaccine. There is no mention of testing the 2nd Generation vaccine, nor acknowledgement a chimpanzee-blood version ever existed, so points #2 and #3 are irrelevant. Point 1 does apply as formalin was added to Lot 751 to kill any unknown viruses, and so the claim that “0.01% formaldehyde, completely inactivated all isolates of the AIDS virus” is routinely cited as proof Lot 751 could not have transmitted HIV. However, one year before that paper, in another paper directed at scientists, the CDC wrote: “Formalin at 0.10% [i.e. 10 times the concentration] was found to reduce reverse transcriptase activity, but complete inactivation was not achieved after 2 hr of exposure.”[109]

Other scientists concurred, writing: “The authors of candidate vaccines have used either thermal inactivation or formol treatment for this purpose. However, experimental data accumulated during the last few years suggests these methods may not be fully reliable.”[110]

Further, after the vaccines were already being administered, the WHO wrote “The question which now looms large is how to ensure that the current candidate hepatitis vaccines are free of these viruses.”[111]

Claim 12

The CDC implied comparable HIV rates in their vaccine vs placebo trial participants, but their only breakdown showed 42% vs 9%.

In 1984 the CDC wrote: “Concern has been expressed that the etiologic agent of AIDS might be present in the vaccine and survive the inactivation steps used in the manufacturing procedure.”[83] Unlike the paper referenced in the prior claim, this one claimed to settle the matter by “monitoring rates of AIDS in groups of homosexually active men who did or did not receive HB vaccine in the vaccine trials conducted by CDC in Denver, Colorado, and San Francisco, California.” The only men “in the vaccine trial” who did not receive vaccine are the placebo group half who declined it post-trial. It is irrefutable that this would settle the matter. But, then the CDC moved the goalpost by comparing “the rate of AIDS for HB vaccine recipients in CDC vaccine trials among homosexually active men in Denver and San Francisco does not differ from that for men screened for possible participation in the trials but who received no HB vaccine because they were found immune to HB.”

Why compare transmission rates between a group selected for not having an STD history against one excluded for having one, when the trial included a random placebo group with identical risk factors? The trial documents expressly state causation can only be determined by comparing against placebo as the "gross bias" of comparing against those who did not participate are "too well known to warrant further discussion”.[26]

The group who were previously infected with HB and “found immune to HB” were called a “higher group” risk because their “behaviors that increased the risk for hepatitis B virus transmission also increased the risk for acquired immunodeficiency syndrome.”[62]

Only one document breaks down the HIV rates by vaccine and placebo groups. In that subset, which included almost half the unvaccinated placebo group, HIV rates were precisely dose dependent[112]:

Claim 13

Robert Garry of “Proximal Origins” claimed 2 ancient HIV+ samples exonerated vaccines. The 1st was exposed as a hoax and retracted. The 2nd was “inadvertently destroyed”.

Dr. Garry received grants to study historic unexplained deaths, and in 1990 reported in Nature: “Two recent news items in Nature highlight the case history of a 25-year-old seaman who died in Manchester, England, of Pneumocystis carinii, and in retrospect, of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection…. We documented HIV-1 infection in a 15-year-old

black male admitted to St. Louis City Hospital in 1968… Western blot analysis of frozen serum and antigen capture enzyme-linked immunoassay of stored tissues confirmed infection with HIV-1.”[113] Dr. Garry subsequently received $17 million in grants for AIDS research per NIH RePORTER.

However, independent DNA testing proved the first sample actually belonged to a contemporary AIDS patient.[114], [115] The last known samples of the second were in Dr. Garry’s lab and “inadvertently destroyed”.[116]

Claim 14

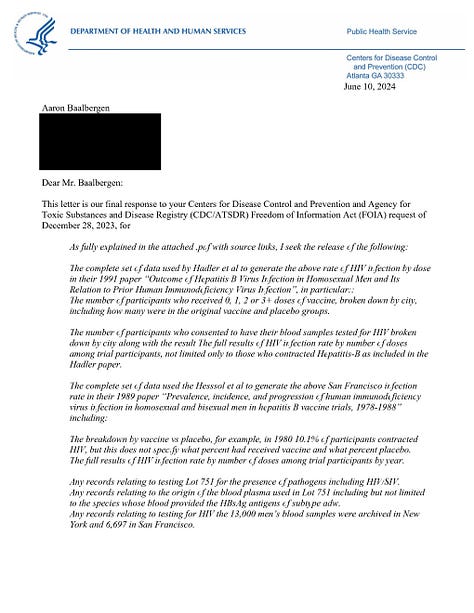

The CDC now claims they cannot locate the trial data they claimed exonerated the vaccine.

In 2023 Fact Mission filed a Freedom of Information Request with the CDC for the trial data. The CDC responded it had “no records”. In response to my appeal, the Director of FOIA Appeals and replied “your appeal falls under ‘unusual circumstances’ in that our office will need to consult with another office or agency that has substantial interest in the determination of the appeal.”

Scientists involved in the trial have privately confirmed having access to the trial data, but claim releasing it is problematic. During the “Factor VIII” litigation, the only way victims obtained documents was through a civil lawsuit, granting rights to deposition and discovery. Scientists could not respond “no comment” and officials “no records found”.

Conclusion

Dismissing counter-narratives without proper consideration fosters a toxic divide, pitting “conspiracy theorists” against “gullible credulists.” In the case of AIDS origins, this has led some to believe that AIDS was a sinister government plot to eradicate marginalized groups, while others dismiss these views as anti-science conspiracies.

There must be common ground to address these divisions constructively. Therefore, this paper is divided into 14 specific claims, allowing scientists to clearly state which claims they dispute and which they concede. This approach enables both sides to focus on the contested areas, fostering dialogue and understanding. Ultimately, the goal is to bridge the divide, finding areas of agreement or, at the very least, agreeing to disagree on specific points.

The rumors around vaccine introduction of AIDS could likely be settled if:

The New York Blood Center provides an accounting of the chimpanzee antigens shipped including the vaccine lot numbers and administration sites where they were used.

The New York Blood Center and CDC release the full trial data including the HIV rate broken down by vaccine and placebo recipients.

Involved scientists should present a paper explaining their rationale for determining the “flareups” were “bound to appear in higher numbers in the vaccine group.”

References

[1] W. Bogdanich and E. Koli, “2 Paths of Bayer Drug in 80’s: Riskier One Steered Overseas,” The New York Times, May 22, 2003. Accessed: Jul. 05, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.nytimes.com/2003/05/22/business/2-paths-of-bayer-drug-in-80-s-riskier-one-steered-overseas.html

[2] J. Dao, “Pataki Signs Bill Letting Hemophiliacs Sue Companies Over Blood-Clotting Products,” The New York Times, Dec. 02, 1997. Accessed: Jul. 05, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.nytimes.com/1997/12/02/nyregion/pataki-signs-bill-letting-hemophiliacs-sue-companies-over-blood-clotting.html

[3] G. N. Vyas, S. N. Cohen, and R. Schmid, Viral Hepatitis: A Contemporary Assessment of Etiology, Epidemiology, Pathogenesis, and Prevention : Proceedings of the Second Symposium on Viral Hepatitis, University of California, San Francisco, March 16-19, 1978. Franklin Institute Press, 1978.

[4] G. WHO/IABS Symposium on Viral Hepatitis (2nd : 1982 : Athens, Second WHO/IABS Symposium on Viral Hepatitis : standardization in immunoprophylaxis of infections by hepatitis viruses : proceedings of a symposium. Basel ; New York : S. Karger, 1983. Accessed: Jul. 08, 2024. [Online]. Available: http://archive.org/details/secondwhoiabssym0000whoi

[5] J. Goodfield, Ed., Quest for the Killers. Boston, MA: Birkhäuser Boston, 1985. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4684-6743-7.

[6] H. Liehr, R. Seelig, and H. P. Seelig, “Cutaneous papulo-vesicular eruptions in non-A, non-B hepatitis,” Hepatogastroenterology., vol. 32, no. 1, pp. 11–14, Feb. 1985.

[7] D. Lieming, Z. Mintai, W. Yinfu, Z. Shaochon, K. Weiqin, and R. A. Smego, “A 9-Year Follow-Up Study of the Immunogenicity and Long-Term Efficacy of Plasma-Derived Hepatitis B Vaccine in High-Risk Chinese Neonates,” Clin. Infect. Dis., vol. 17, no. 3, pp. 475–479, Sep. 1993, doi: 10.1093/clinids/17.3.475.

[8] G. Ji, R. Detels, Z. Wu, and Y. Yin, “Correlates of HIV infection among former blood/plasma donors in rural China,” AIDS, vol. 20, no. 4, pp. 585–591, Feb. 2006, doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000210613.45212.c4.

[9] O. W. Prozesky et al., “Baseline epidemiological studies for a hepatitis B vaccine trial in Kangwane”.

[10] O. W. Prozesky et al., “Immune response to hepatitis B vaccine in newborns,” J. Infect., vol. 7, pp. 53–55, Jul. 1983, doi: 10.1016/S0163-4453(83)96649-5.

[11] S. Cross and A. Whiteside, Facing up to AIDS: The Socio-Economic Impact in Southern Africa. Springer, 2016.

[12] B. S. Blumberg and I. Millman, “Vaccine against viral hepatitis and process,” US3636191A, Jan. 18, 1972 Accessed: Jul. 05, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://patents.google.com/patent/US3636191A/en

[13] W. SZMUNESS and A. M. PRINCE, “THE EPIDEMIOLOGY OF SERUM HEPATITIS (SH) INFECTIONS: A CONTROLLED STUDY IN TWO CLOSED INSTITUTIONS12,” Am. J. Epidemiol., vol. 94, no. 6, pp. 585–595, Dec. 1971, doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a121357.

[14] F. Deinhardt and I. D. Gust, “Viral hepatitis,” Bull. World Health Organ., vol. 60, no. 5, pp. 661–691, 1982.

[15] J. E. Maynard, K. R. Berquist, D. H. Krushak, and R. H. Purcell, “Experimental Infection of Chimpanzees with the Virus of Hepatitis B,” Nature, vol. 237, no. 5357, pp. 514–515, Jun. 1972, doi: 10.1038/237514a0.

[16] V. J. McAuliffe, R. H. Purcell, and J. L. Gerin, “Type B Hepatitis: A Review of Current Prospects for a Safe and Effective Vaccine,” Clin. Infect. Dis., vol. 2, no. 3, pp. 470–492, May 1980, doi: 10.1093/clinids/2.3.470.

[17] A. M. Prince, J. Vnek, R. A. Neurath, and C. Trepo, “Vaccine manufacture for active immunization containing hepatitis B surface antigen and associated antigen,” US4118478A, Oct. 03, 1978 Accessed: Jul. 05, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://patents.google.com/patent/US4118478A/en?oq=4%2c118%2c478

[18] J. Vnek, H. Ikram, and A. M. Prince, “Heterogeneity of hepatitis B surface antigen-associated particles isolated from chimpanzee plasma,” Infect. Immun., vol. 16, no. 1, pp. 335–343, Apr. 1977, doi: 10.1128/iai.16.1.335-343.1977.

[19] W. Szmuness, C. E. Stevens, E. A. Zang, E. J. Harley, and A. Kellner, “A controlled clinical trial of the efficacy of the hepatitis B vaccine (heptavax B): A final report,” Hepatology, vol. 1, no. 5, pp. 377–385, Sep. 1981, doi: 10.1002/hep.1840010502.

[20] B. A. Koblin, J. M. Morrison, P. E. Taylor, R. L. Stoneburner, and C. E. Stevens, “Mortality Trends in a Cohort of Homosexual Men in New York City, 1978–1988,” Am. J. Epidemiol., vol. 136, no. 6, pp. 646–656, Sep. 1992, doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116544.

[21] J. Vnek et al., “Cryptic association of e antigen with different morphologic forms of hepatitis B surface antigen,” J. Med. Virol., vol. 4, no. 3, pp. 187–199, 1979, doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890040305.

[22] J. Vnek, A. M. Prince, N. Hashimoto, and H. Ikram, “Association of normal serum protein antigens with chimpanzee hepatitis B surface antigen particles,” J. Med. Virol., vol. 2, no. 4, pp. 319–333, 1978, doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890020405.

[23] Ap, “HEALTH EXPERTS START CAMPAIGN ON HEPATITIS,” The New York Times, Dec. 16, 1984. Accessed: Jul. 10, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.nytimes.com/1984/12/16/us/health-experts-start-campaign-on-hepatitis.html

[24] J. Vnek and A. M. Prince, “Large scale purification of hepatitis type B antigen using polyethylene glycol,” US3951937A, Apr. 20, 1976 Accessed: Jul. 05, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://patents.google.com/patent/US3951937A/en

[25] P. A. Offit, Vaccinated: One Man’s Quest to Defeat the World’s Deadliest Diseases, Reprint edition. Harper Perennial, 2008.

[26] W. Szmuness, “Large‐scale efficacy trials of hepatitis B vaccines in the USA: Baseline data and protocols,” J. Med. Virol., vol. 4, no. 4, pp. 327–340, Jan. 1979, doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890040411.

[27] D. P. Francis, “The Prevention of Hepatitis B with Vaccine: Report of the Centers for Disease Control Multi-Center Efficacy Trial Among Homosexual Men,” Ann. Intern. Med., vol. 97, no. 3, p. 362, Sep. 1982, doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-97-3-362.

[28] R. A. Coutinho et al., “Efficacy of a heat inactivated hepatitis B vaccine in male homosexuals: outcome of a placebo controlled double blind trial.,” BMJ, vol. 286, no. 6374, pp. 1305–1308, Apr. 1983, doi: 10.1136/bmj.286.6374.1305.

[29] J. P. Soulier and A. M. Courouce, “Progrès concernant les hépatites virales,” Rev. Fr. Transfus. Immuno-Hématologie, vol. 24, no. 5, pp. 501–517, Nov. 1981, doi: 10.1016/S0338-4535(81)80199-7.

[30] H. W. Reesink et al., “Heat-inactivated HBsAg as a vaccine against hepatitis B,” Antiviral Res., vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 13–25, Mar. 1981, doi: 10.1016/0166-3542(81)90028-0.

[31] A. A. McLean, M. R. Hilleman, W. J. McAleer, and E. B. Buynak, “Summary of worldwide clinical experience with H-B-Vax® (B, MSD),” J. Infect., vol. 7, pp. 95–104, Jul. 1983, doi: 10.1016/S0163-4453(83)96879-2.

[32] B. L. Murphy, J. E. Maynard, and G. Le Bouvier, “Viral Subtypes and Cross-Protection in Hepatitis B Virus Infections of Chimpanzees,” Intervirology, vol. 3, no. 5–6, pp. 378–381, 1974, doi: 10.1159/000149775.

[33] M. H. Poleski, “Kaposi’s sarcoma and hepatitis B vaccine,” Ann. Intern. Med., vol. 97, no. 5, pp. 786–787, Nov. 1982, doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-97-5-786_3.

[34] “No Increased Incidence of AIDS in Recipients of Hepatitis B Vaccine,” N. Engl. J. Med., vol. 308, no. 19, pp. 1163–1164, May 1983, doi: 10.1056/NEJM198305123081914.

[35] 2016.500.17 Don Francis, (Nov. 03, 2017). Accessed: Jul. 09, 2024. [Online Video]. Available: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AHodp4k_GsQ

[36] D. C. D. Jarlais et al., “HIV-1 Infection Among Intravenous Drug Users in Manhattan, New York City, From 1977 Through 1987”.

[37] R. A. Weiss, D. Whitby, S. Talbot, P. Kellam, and C. Boshoff, “Human Herpesvirus Type 8 and Kaposi’s Sarcoma,” JNCI Monogr., vol. 1998, no. 23, pp. 51–54, Apr. 1998, doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jncimonographs.a024173.

[38] M. Worobey et al., “1970s and ‘Patient 0’ HIV-1 genomes illuminate early HIV/AIDS history in North America,” Nature, vol. 539, no. 7627, pp. 98–101, Nov. 2016, doi: 10.1038/nature19827.

[39] R. M. Henig, “AIDS A NEW DISEASE’S DEADLY ODYSSEY,” The New York Times, Feb. 06, 1983. Accessed: Jul. 08, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.nytimes.com/1983/02/06/magazine/aids-a-new-disease-s-deadly-odyssey.html

[40] M. S. Gottlieb et al., “Pneumocystis carinii Pneumonia and Mucosal Candidiasis in Previously Healthy Homosexual Men: Evidence of a New Acquired Cellular Immunodeficiency,” N. Engl. J. Med., vol. 305, no. 24, pp. 1425–1431, Dec. 1981, doi: 10.1056/NEJM198112103052401.

[41] H. Masur et al., “An Outbreak of Community-Acquired Pneumocystis carinii Pneumonia,” N. Engl. J. Med., vol. 305, no. 24, pp. 1431–1438, Dec. 1981, doi: 10.1056/NEJM198112103052402.

[42] “Pneumocystis Pneumonia --- Los Angeles.” Accessed: Jul. 08, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/june_5.htm

[43] L. K. Altman, “RARE CANCER SEEN IN 41 HOMOSEXUALS,” The New York Times, Jul. 03, 1981. Accessed: Jul. 05, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.nytimes.com/1981/07/03/us/rare-cancer-seen-in-41-homosexuals.html

[44] “PAHO/ACMR 15/16 Pan American Health Organization FIFTEENTH MEETING OF THE ADVISORY COMMITTEE ON MEDICAL RESEARCH.” CARIBBEAN EPIDEMIOLOGY CENTRE, Jun. 14, 1976. [Online]. Available: https://iris.paho.org/bitstream/handle/10665.2/47317/ACMR15_16.pdf

[45] “Private communication from a scientist working with Alfred Prince in the 1970’s at NYBC’s VILAB II in Liberia.”

[46] E. M. Gaillard, “Understanding the reasons for decline of HIV prevalence in Haiti,” Sex. Transm. Infect., vol. 82, no. suppl_1, pp. i14–i20, Apr. 2006, doi: 10.1136/sti.2005.018051.

[47] M. Simons, “FOR HAITI’S TOURISM, THE STIGMA OF AIDS IS FATAL,” The New York Times, Nov. 29, 1983. Accessed: Jul. 08, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.nytimes.com/1983/11/29/world/for-haiti-s-tourism-the-stigma-of-aids-is-fatal.html

[48] N. A. Hessol et al., “Progression of Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 (HIV-1) Infection among Homosexual Men in Hepatitis B Vaccine Trial Cohorts in Amsterdam, New York City, and San Francisco, 1978–1991,” Am. J. Epidemiol., vol. 139, no. 11, pp. 1077–1087, Jun. 1994, doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116951.

[49] P. Lemey, O. G. Pybus, B. Wang, N. K. Saksena, M. Salemi, and A.-M. Vandamme, “Tracing the origin and history of the HIV-2 epidemic,” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci., vol. 100, no. 11, pp. 6588–6592, May 2003, doi: 10.1073/pnas.0936469100.

[50] W. Carswell, “HIV in South Africa,” The Lancet, vol. 342, no. 8864, p. 132, Jul. 1993, doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)91342-J.

[51] C. Rudin, R. Berger, R. Tobler, P. W. Nars, M. Just, and N. Pavic, “HIV-1, hepatitis (A,B, and C), and measles in Romanian children,” The Lancet, vol. 336, no. 8730, pp. 1592–1593, Dec. 1990, doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)93380-8.

[52] F. Popovici et al., “Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome in Romania,” The Lancet, vol. 338, no. 8768, pp. 645–649, Sep. 1991, doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)91230-R.